Donald Judd Drawings: © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York/DACS, London 2012 Installation Views: Working Papers: Donald Judd Drawings, 1963 - 93, installation view, Sprüth Magers London, January 2012. © Photography Stephen White.

The exhibition of Donald Judd’s workings drawing that opened at Sprüth-Magers on Thursday continues something of a theme in the gallery’s programming of late. In a turn that has not gone unremarked, almost half of Sprüth’s London shows since last February’s (quite literally) illuminating exhibition of Anthony McCall’s ‘Works on Paper’ have featured the sketches, working drawings and documentation various of big-name artists including Joseph Kosuth, George Condo and of course Judd himself.

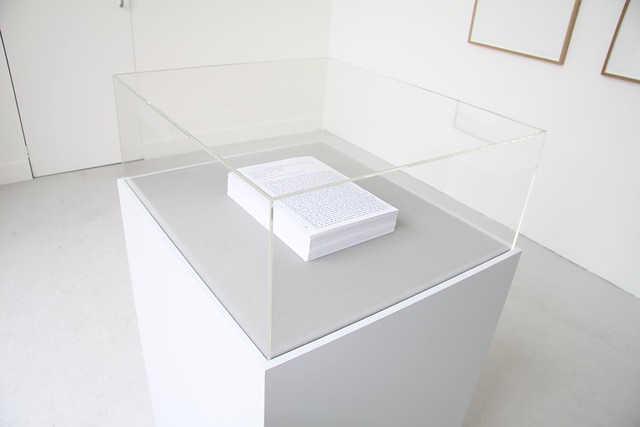

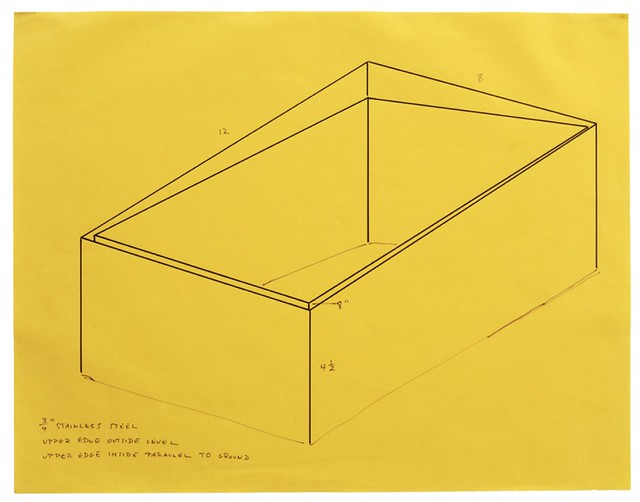

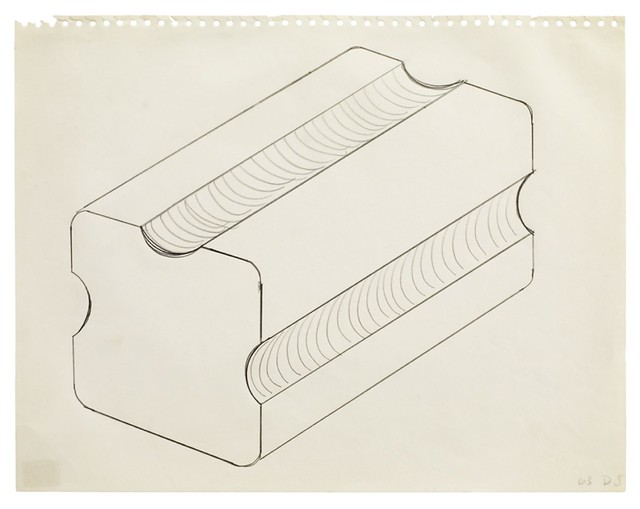

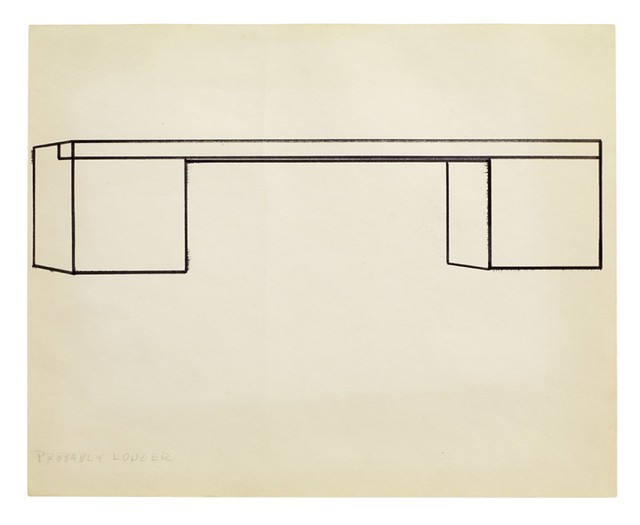

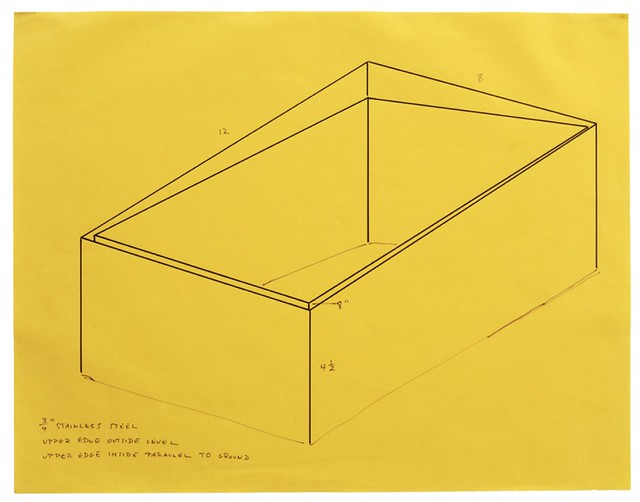

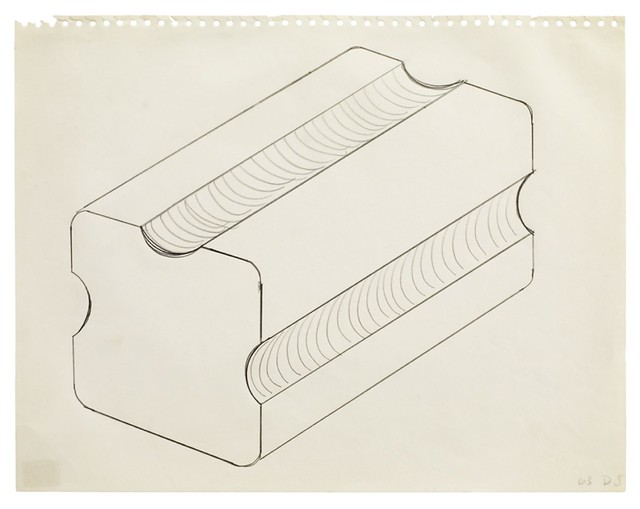

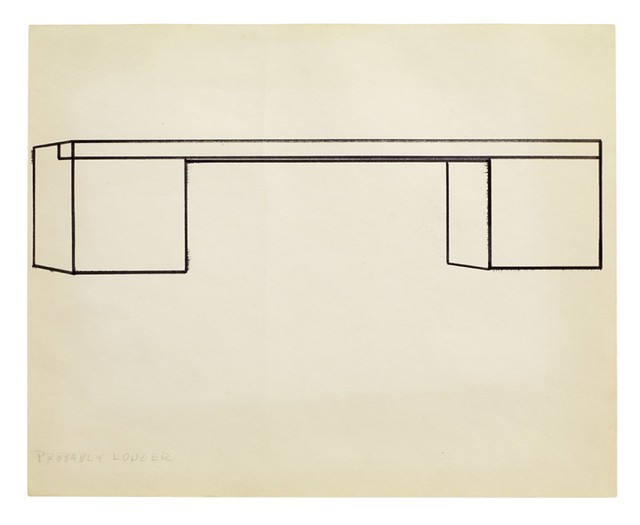

Whilst this current emphasis on the ephemeral might summon such metaphors as ‘scraping the barrel’ to the mind of the more cynical observer, the interest of these shows should not be dismissed outright. Working Papers brings together 33 preliminary sketches outlining the sculptural works for which Judd is best known. The most interesting of these are on headed order forms submitted by Judd to his contractors, the steel companies and metal-works that produced the objects with which he made his name.

The old question rears its head: what’s in a name? At what point does object become sculpture, producer become artist? Casual in their execution but meticulous in their conception, these order forms occupy a position paradoxically closest to the artist – bearing the unique traces of Judd’s hand and therefore an originality that is without equivalent in the finished sculptures – even as they symbolise the contractual displacement of artistic productivity away from him. Some even include a price alongside Judd’s rigorous instructions. As such, there is a certain boldness in Sprüth’s decision to shine a spotlight on those brute (and therefore troubling) technical and economic factors that underpin the creative process but are all too often concealed by it. One need only to consult David Hockney’s recent,

thinly-veiled critique of Damien Hirst to know that this is a question that remains as incendiary within the artistic community as outside it.