All works © Elmgreen & Dragset; Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art; all photos © by Elad Sarig

Having worked together since 1995, the Danish artist Michael Elmgreen and Norwegian artist Ingar Dragset established a collective practice in which they typically sabotage social desires and rituals in public spaces or corrupt the choreography of art institutions and exhibition through interrupting aesthetic expectations. An imaginary dead art collector floating face-down in a pool at the Venice Biennale in The Collectors (2009), Han (2012) a male answer to Copenhagen's little mermaid placed by the seaside in Helsingør or, famously, Prada Marfa (2005), a fake Prada Boutique set in the middle of the Texas' desert – the interventions of the artist duo reveal a satirical and critical view on problematic conditions of power and capital, on social injustice, gender inequality and queer culture, but also on ordinary symbols of society's everyday lives. Their current exhibition Powerless Structures at Tel Aviv Museum of Art in Israel gave reason to speak with Elmgreen & Dragset about denying the audience's desires, demystifying art institutions and a need for unspectacular images in an era of selfie culture.

Anna-Lena Werner: Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, your current exhibit Powerless Structures at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art brings together eight works that address and sometimes corrupt constructed power patterns, attributed to certain structures, objects or social networks. How do you empower these structures?

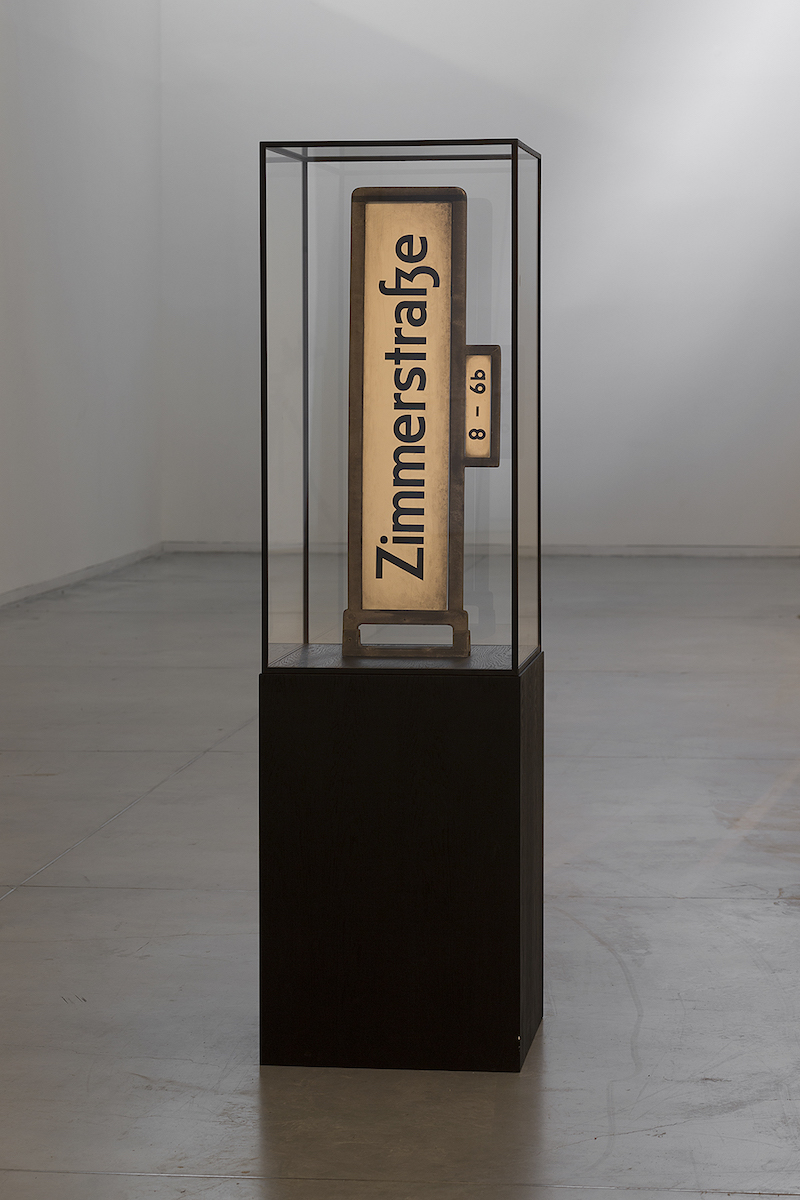

Elmgreen & Dragset: The name of the exhibition, Powerless Structures, is taken from the title of a series of works we started making in 1997. It comes from philosopher Michel Foucault’s ideas that structures themselves cannot impose any power, unless we, as a society, allow them to do so. We’ve taken various contexts, situations, and everyday objects, and adjusted them to disrupt people’s original expectations, thus opening up space for new interpretations.

ALW: There is a biased relation between power structures and the art world – a notion that you seem to refer to in your new installation Other Landscapes (2016): a partially applied wall text and instalment-situation for a fictional Matisse exhibition. Is this a comment on the block-buster programs that many Western art institutions follow?

E&D: No, actually, the Other Landscapes installation stems from a time when we were both in New York and went to see an Iza Genzken show at the Museum of Modern Art. Close to the entrance of Genzken's show was a sign announcing an upcoming Gaugin exhibition, only partly installed on the wall, with ladders and installation equipment scattered around it—we found this to be a marvelous first entrance into a Genzken show. However, it turned out this was not a staged reality, but the actual installation of a forthcoming show in preparation at MoMA at the time. The visual impression and the concept of using an announcement of another artist’s show as your own artwork nevertheless stayed with us, and for Tel Aviv we used the name Matisse—a reference to the lack of any works by Matisse in the museum’s collection, something we discovered through our dialogues with the museum curator and director. There had been a moment in time when the museum considered such an exhibition, but due to logistics and funding, it never happened.

Other than that, the work can be seen in line with earlier works, such as Between Other Events at Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst in Leipzig, where we extended the renovation period that normally happens between exhibitions into lasting through—and becoming – the exhibition itself. Two house painters painted the white walls white over and over again for weeks. We like bringing the behind the scenes up front, thereby demystifying some of the exclusive aura around museums and institutions.

ALW: The work Donation Box (2006) contains waste and a few random objects, such as a car key or a dummy, rather than actual money. On top of that, it's sealed, making it impossible for visitors to add anything into the glass box. While formally the work thus touches on the subject of inaccessibility and value or currency, it also positions the act of donating in a context of power structures. Could you explain how you read this particular work?

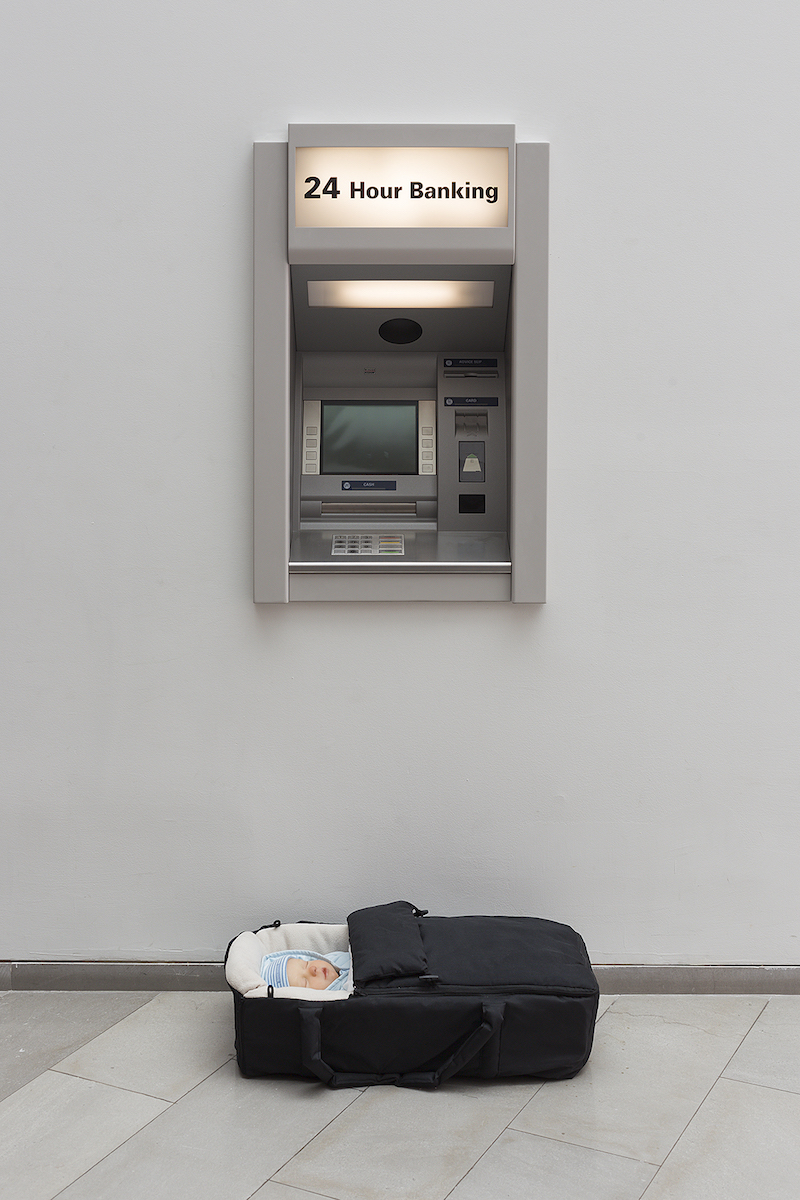

E&D: To us, this work is about a sort of personal currency within an institutional framework. It shows people’s various personal effects—in addition to, but also besides, money—giving some clues to their identities, which are then in turn, linked back to an institution by their presence in the donation box. We wanted to physically manifest this complex interplay in an impossibly sealed transparent case, exposing it for all to see. Donation Box is one of our ‘denial works’ where the audience is seemingly invited to partake in an action, but is then denied the fulfilment of this action. These are attempts to disrupt logic, expectation, and intuition, and hopefully generate a productive frustration.

In its very basic essence though, the work questions the system of funding. We are experiencing more and more donation boxes coming up in public institutions, which is a sign that attitudes towards private funding, as opposed to taxation and public funding, are changing.

ALW: There is a link between Donation Box and Wishing Well/Powerless Structures, Fig. 166 (2016), a sealed pool with blank coins, located in the museum’s sculpture garden. Why did you choose to stage the power structure of money in relation to social rituals of donating or superstitious wishing?

E&D: The way we spend our money, the things that we wish for: these are reflections of our inner desires, which, though they vary from person to person, also link us all together. Both of these works are sealed or blocked in some way; they are further examples of the ‘denial works’ that we mentioned before. Other examples of works like this include Prada Marfa—a closed Prada store in the Texan desert—and Powerless Structures, Fig. 11—a diving board penetrating the window of the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk.

ALW: Powerless Structures is your first exhibition in Israel. With the site-specific installation For as Long as It Lasts (2016) you invaded the museum space with a a one to one replica of the Berlin wall. Does this work also draw a relation to the separation between two geographic entities, as it happened in Berlin and still happens between Israel and Palestine? Are bricked borders a repetitive power structure?

E&D: For us, the Berlin Wall is personally significant, as we decided to move to Berlin as a direct result of the fall of the wall. In many ways this structure has played a large part in our development as artists. That being said, despite the physical resemblance to the Berlin Wall, the installation functions as a blank surface for projection, which will vary according to the individual spectator. The title For as Long as It Lasts refers to the ultimately temporary nature of structures imposed upon people against their will. The title also hints to relationships that may not be sustained over time; pain that could go away; and the disposable nature of certain objects – those made in cheap materials last, simply, as long as they last.

The work seems to have gained new relevance within the past few months, with the changing policies of many European countries in light of increased immigration, and with the U.S. presidential election campaign, in which some candidates are strongly advocating for a wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

ALW: Behind the large wall installation you positioned the sculpture of a teenage boy sitting on a high fire escape without full access to the ground. He literally sits behind bars, imprisoned in the metal balcony structure, and supposedly in his life structures, too. Why is The Future (2014) – as the work is called – so hopeless and cheerless?

E&D: This exhibition in Tel Aviv is the third and final part of our exhibition series called Biography, for which The Future was initially created. The work was presented first at the Astrup Fearnley Museum in Oslo, and then at the National Gallery of Denmark in Copenhagen. Like many of our other works, and especially in light of the current “selfie” craze on social media, we wanted to make something that was more introspective, focused on calm, quiet moments of reflection, something not spectacular, that’s intimate and not necessarily shiny and happy. We cannot predict the future; we do not yet know what is in store for younger generations, like the teenager seated on the fire escape. Growing up is always painful.

Elmgreen & Dragset

1st of April - 27th of August 2016

27 Shaul Hamelech Blvd

POB 33288

The Golda Meir Cultural and Art Center

61332012 Tel Aviv, Israel

Opening Hours: Mon + Wed + Sat 10-18h, Tues + Thurs 10-21h, Fri 10-14h, Sun Closed

All works © Elmgreen & Dragset; Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art; all photos © by Elad Sarig

All works © Elmgreen & Dragset; Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art; all photos © by Elad Sarig

All works © Elmgreen & Dragset; Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art; all photos © by Elad Sarig

All works © Elmgreen & Dragset; Courtesy Tel Aviv Museum of Art; all photos © by Elad Sarig