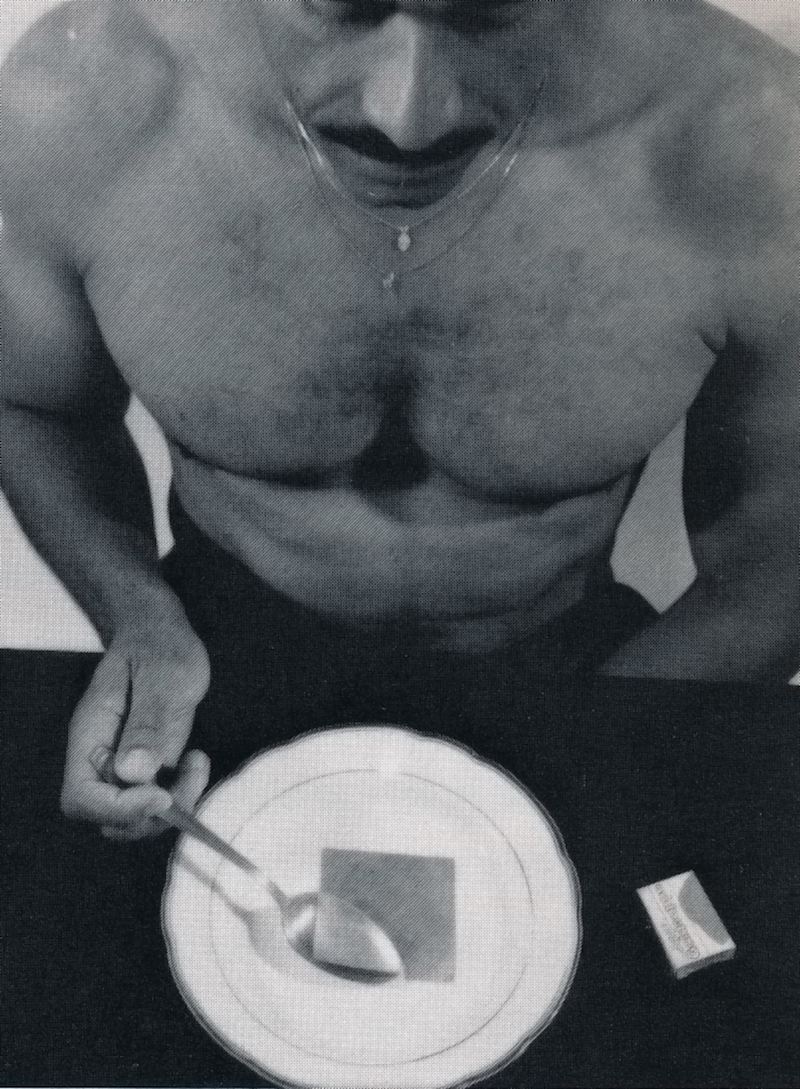

WERKSTADT Graz "Baur`s Goldsuppe", Photo: Amy Harris. from the catalogue "JEWELRY: MEANS: MEANING"

WERKSTADT Graz "Baur`s Goldsuppe", Photo: Amy Harris. from the catalogue "JEWELRY: MEANS: MEANING"

The city of Graz is rich on avant-garde history in contemporary art that emerged in the 1960s and experienced one of its peaks in the 1980s. A strong connection to Cologne and the group of the Neue Wilden, as well as to the Viennese performance artists carried out by galleries such as Galerie Bleich-Rossi and Artelier shaped the cultural scene. It was also the moment when international Jazz musicians were frequenting the city. The trigon biennial for contemporary art and architecture, as well as the avant-garde festival for performance and visual arts steirischer herbst had become milestones of pioneering artistic positions since their launch in the 1960s. One of the core players from that time and still active today is WERKSTADT Graz – a gallery and an interdisciplinary project space, often working in the field of relational aesthetics. I talked to Barbara Edlinger, co-founder, artist and goldsmith about the history and the vision of WERKSTADT and her approach towards today’s cultural production in the city.

Helene Romakin: WERKSTADT as an established and historical institution in Graz carries out different functions in arts, craftsmanship and social engagement. Could you tell me more about the founding history and your intentions?

Barbara Edlinger: WERKSTADT was founded in 1987 when we created a space out of personal necessity. Since 1979 Joachim Baur has had his studio in the same building where he also organised exhibitions. From the beginning, we worked as an interdisciplinary artist collective and wanted to have a space where we would feel appreciated in our practice. Beside artistic practice WERKSTADT was devoted to the art of jewellery [Schmuckkunst]. Thinking about gold as a metaphor of values and Gestaltung, in the sense of design and formation in handy size, was Joachim Baur’s subject. He worked with gold and hence, with money—an affinity towards such unimpeachable material, which back then was still uncommon and widely puzzling. By emphasizing the coherence with socially relevant positions these works reached out of his studio to the public sphere. For this innovative combination of diverse perspectives on art and craftsmanship we didn’t find any place in Graz: Neither were we pure artisans nor involved in the gallery scene of the Neue Wilden.

HR: The play on words implied in the name of WERKSTADT – referring to both a work city and a workshop – poses questions to the geographic importance of the institution. What was your intention behind it?

BE: We played with the word Werkstatt/-stadt, which bears this exact ambiguity: The workshop as a place where art is produced and thus, is associated with artistic activity. So, it is an artist atelier and simultaneously, it is the city, the urban space as such. We chose the term, in order to literally intervene in the city space understanding the city as our studio. This was the moment where we decided to follow this specific work order engaging with social structure within the society. Back in the space of WERKSTADT, we could present our results from this research. Our goal was and still is to be an institution with a strong socio-political standing as well as an artist collective with pioneering projects. The exchange outside borders was always essential to our work. Over the years, we have built a wide network with international artists from different continents with whom we have worked in various spaces.

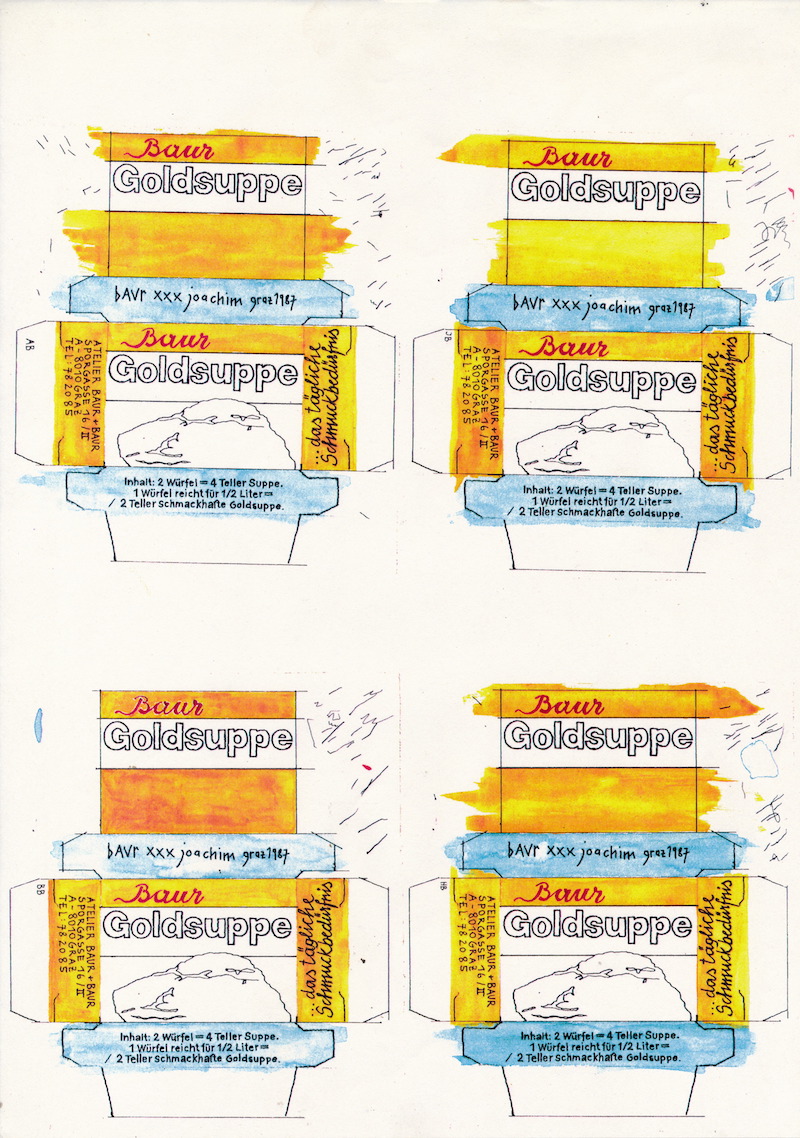

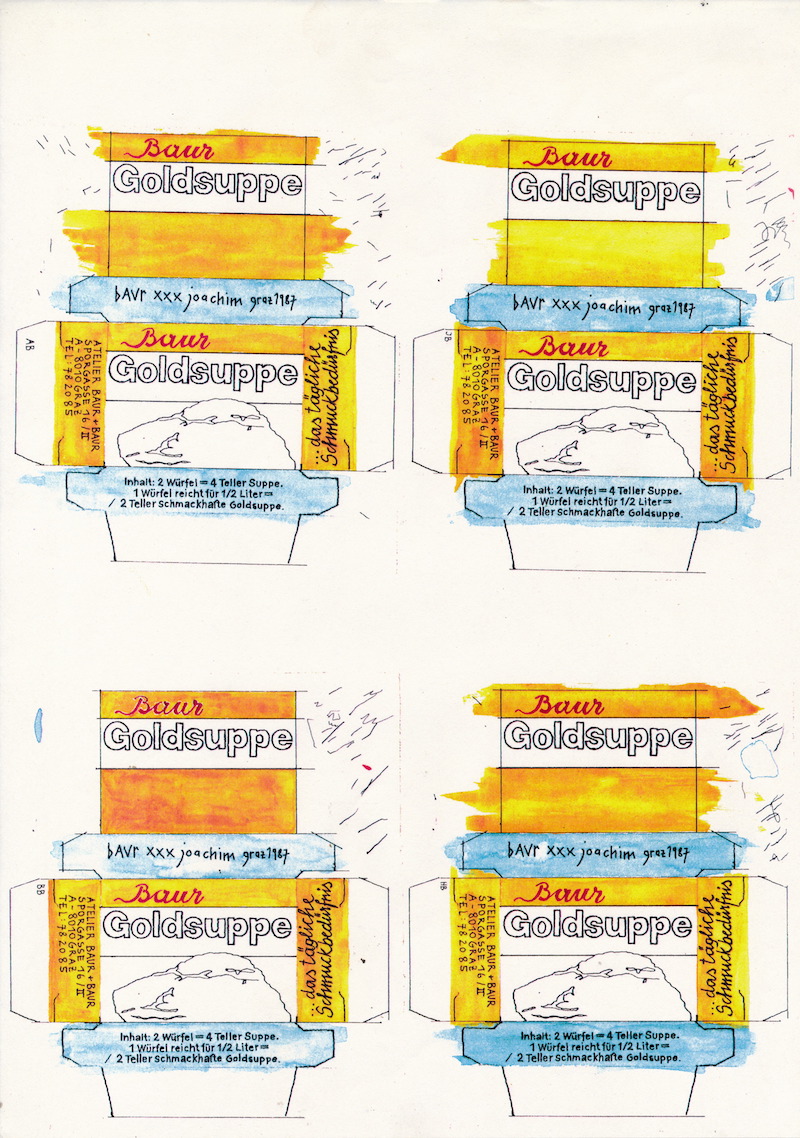

WERKSTADT Graz, "Baur`s Goldsuppe", drafts

WERKSTADT Graz, "Baur`s Goldsuppe", drafts

WERKSTADT Graz, "Baur`s Goldsuppe", drafts

WERKSTADT Graz, "Baur`s Goldsuppe", drafts

HR: Could you tell me about your first interdisciplinary projects?

BE: Our first inspirations derived from food. The theme of the kitchen arose from our research on the term Geschmack [taste]. Also, at that time we often produced Schmuck [jewellery]. Having the stem of Schmuck, Geschmack and schmecken [to taste] so close to each other served Joachim Baur as an initial point to address word plays and existing meaning structures. We juxtaposed the ideas behind Schmuck and Geschmack in our project about the popular instant soup called “Knorrs-Goldaugen-Würfel-Suppe” [Knorr's-Golden-Eyes-Cube-Soup] that was sold as cubes packed in golden paper. Together with Joachim Baur, I realised a work under the title “Baur’s Golden Eyes Beef Soup,” where we mixed the cubes with beatgold and designed the packaging just in the same style of the original product only modifying the name.The immanent questions what I take into my body, with what do I decorate myself, wherewith I nourish, contained also an ironic metabolism: By eating the golden soup, you were giving back the gold to the earth. Giving the gold back to the planet, this is still an essential occupation in Joachim Baur’s work.

HR: When did you start working in the public space?

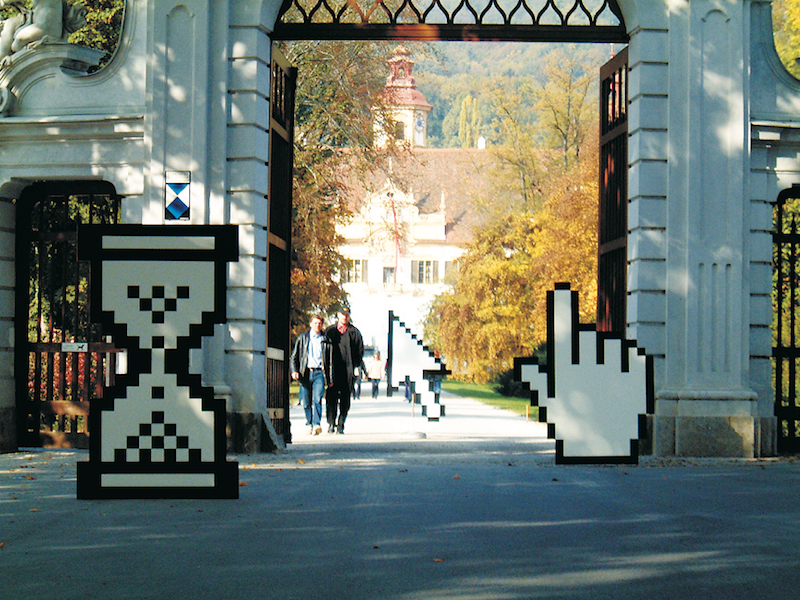

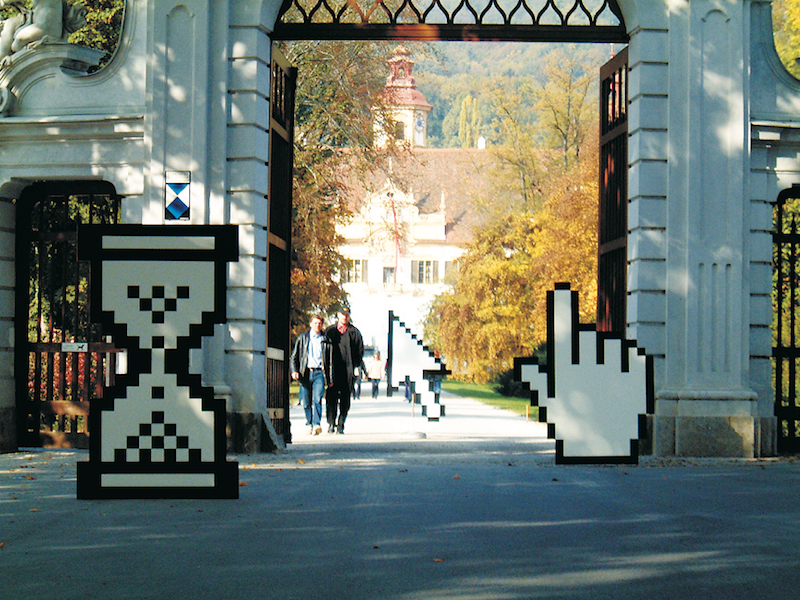

BE: One of our biggest projects in public space was the Graz Marathon. Over a period of 10 years, we were artistically engaged in the marathon run by designing the medal. In 2000 the city councillor in charge of cultural affairs asked Joachim Baur to design a medal for the marathon. The commission was obviously based on the assumption: “He realises unconventional projects but at least he is a craftsman, he will conceive a proper golden medal.” Well, we did a medal: a CD to hang around your neck. This CD was an artwork with collected scientific, philosophic and artistic contributions to subjects such as philosophy, art, body and sports. Every runner received this medal with a note of their personal running time. It was not about a ranking hierarchy anymore, but rather about the equivalence of every participant. Beside the idea of a medal for everyone, we also created a specific context through art, which allowed further philosophical and scientific reflection on the event. In addition, we placed oversized sculptures in form of an hourglass, a forefinger and an arrow (a 1:1 translation of the Windows Program signs) alongside the marathon. This was the connection between the real and digital space, on the one hand the medal as a digital storage media, and digital icons in form of real sculpture on the other. It was very amusing to realise that some of the runners waited every year for the next medal and others, didn’t even notice that you could play the CD.

Grazer Marathon, WERKSTADT Graz, 2003, Photo: Seiichi Furuya

Grazer Marathon, WERKSTADT Graz, 2003, Photo: Seiichi Furuya

Grazer Marathon, WERKSTADT Graz, 2003, Photo: Seiichi Furuya

Grazer Marathon, WERKSTADT Graz, 2003, Photo: Seiichi Furuya

HR: Some projects, which combined the artisanal with a social engagement, operated around joint cooking, eating and dressing. Let’s speak about your first project on food “Teranga.”

BE: The project “Teranga” was a reflection or rather an answer to the problems of the prevailing asylum policy, which one could already sense in the beginning of the 2000s. We were asking ourselves, how can we react to this situation as artists and how do we deal with it in a creative way? So we re-arranged our gallery space into a restaurant. You have to know, the space is not big at all. It is a small tripartite room: One part was transformed into a kitchen, the middle room functioned as a bar and all around we placed small tables so that around 20 people could find a seat. For the project we employed two asylum seekers from Senegal as artists in the kitchen. Back then this was still possible by doing bureaucratic detours. We conducted this initiative as an art project for seven years. We never had an official permission as a restaurant, but we succeeded to build a parallel world as an image, which symbolised a possibility how to eat and cook together. We designed our own menu with new terms for different dishes. The Euro was defined as “a voluntary gift for food” and so on…

HR: What was the general outcome of this project?

BE: We were especially excited that Renate Wiehager from the Daimler Art Collection came to Graz and rewarded us with an Art Prize. As a result, further kitchens took place at the Neue Galerie Graz, and later the WERKSTADT Kitchen at the Stadtmuseum Wels. Because of this award one of the cooks received the Austrian nationality. Today, he lives with his family in Graz.

HR: Was cooking his original professional?

BE: No! He actually learned it for the project. This situation was very interesting in general, since he was so strongly engaged – for a man from Senegal to cook was not usual at all. However, he learned very quickly and in a very kind manner. And, from this experience he built a beautiful communication to his relatives in Senegal, since he was constantly calling different women from his native circle in order to ask for recipes. “Teranga” meaning “Welcome to Freedom” was an African restaurant with Senegal kitchen, which had an impact on both cultures involved. In 2003 when Graz was the European Capital of Culture, “Teranga” was the favourite place of Henning Mankell. He realised a big project at the Schauspielhaus Graz and was a regular visitor during his residence. Also, Mankell gave an interview for an art magazine in the Austrian TV that was filmed in the restaurant. It was the place where he decided to be.

HR: After such great and positive experiences, you made further projects in the field of relational aesthetics…

BE: We extended this project to the WERKSTADT Kitchen in Berlin. This time it was a trialogue of the three monotheistic cultures where three cooks from the respective regions were asked to come together. That was the open challenge. We reduced the idea of living together to cooking together. Is it possible at all to cook food from different cultures in one space at a time? It was wonderful to see how the project evolved and how to the idea of eating together was given the priority. New paths were discovered how to cook traditional meals without disturbing the other. It was a feast! After the dinner, we sealed the kitchen and thus, withdrew it from its usage. From there on, it functioned as a sculpture.

KLEIDERWERK, open day, 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir

KLEIDERWERK, open day, 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir

KLEIDERWERK, open day, 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir

KLEIDERWERK, open day, 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir

HR: In the current project “KLEIDERWERK” you work again with refugees. What is the idea behind it?

BE: “KLEIDERWERK” is a tailor shop that is being established with refugee women. In October 2016, we started the project in our gallery space while rearranging the space into a tailor shop. The core idea is based on tailoring, a process, through which social topics such as forced migration and primary integration are revisited and transformed. Crucial to the project are the exchange of experiences, the creation of knowledge and particularly the actual work and thus, the realisation of tangible goals. The first projects were accompanied by my partner Lea Sonnek who, as a trained tailor, was teaching and supervising the participants. Currently we count 15 women from 10 countries with whom we are constantly working. Some of them are already trained, others have basic knowledge from their own practice, and some are acquiring the know-how for the first time. Simultaneously, we are very eager to enable the women to introduce their insights and needs to the team.

HR: Do you pursue any specific goals with this project?

BE: The intention is to foster integration and to create employment through this work, to help the women to find their own place within this context. It is about empowerment of the participants through their practice as tailors and about handling their lives on their own, also financially. But of course, the project questions the concept of identity. With this project, I point out a basic need that interests me. While “Teranga” dealt with a basic need of nourishment, now it is the basic need of clothing, covering and veiling.

KLEIDERWERK, Tote Bags for the Venice Biennale 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir;

KLEIDERWERK, Tote Bags for the Venice Biennale 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir;

KLEIDERWERK, Tote Bags for the Venice Biennale 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir;

KLEIDERWERK, Tote Bags for the Venice Biennale 2017, Photo: Croce & Wir;

below: KLEIDERWERK at the Kunsthaus Graz, Photo: Croce & Wir

HR: Which project have you already accomplished?

BE: The first successful venture of “KLEIDERWERK” was the collaboration with the Austrian Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. For the Biennale we developed a tote bag, on which every member of “KLEIDERWERK” worked on. It is a collaborative product counting many individual ideas and influences. At the opening of the Biennale the bag was an absolute must have, everyone wanted to have it!

HR: All projects mentioned above are based on open-mindedness and togetherness. What does collaboration mean for your practice? Do you see more potential in working together than in a self-optimising work?

BE: Collaboration does not only multiply, but it also exponentiates work, it offers a source of friction and thus, demands different solution approaches. However, the basis is always individual and independent work.

HR: Where do you see the artistic aspiration behind the socially engaged projects?

BE: I see all projects as images. I produce an image. As an artist I deal with creation and interpretation of images. In the moment of realising such a project, I produce an image with real and specific actions. Each detail of the whole picture is precisely reflected. Every image hanging on the wall, every conversation spoken are anchored in this moment in the picture. Once, I defined it as realism. I reckon the projects as realist painting if you take Socialist Realism, or Renaissance Realism. However, it is a realism that expands in and over the space and turns into actions. But still, it stays as a complete picture… From outsiders, my projects were not always perceived as art. Years after “Teranga” was closed, I was called for reservations at the restaurant. Many didn’t even know that it was an art space. Nevertheless, it becomes a protected space in the moment when you call it art. The creation of such a space offers a draft in a certain frame. The moment of art allows us to freely think and engage, to free ourselves from rules and regulations. In such a context it is possible not only to draft but to realise images, ideas and prototypes.

HR: So it is about the power of image that can reveal moments of freedom in reality?

BE: Yes, in fact like a winged altar as an object, which is closed ... but when you open it, you suddenly have an entire space in front of you.

Current exhibition

WERKSTADT / Galerie Crazy, Graz

WERKSTADT / Galerie Crazy, Graz

in collaboration with KLEIDERWERK: Maria Hahnekamp

until 21 October 2017