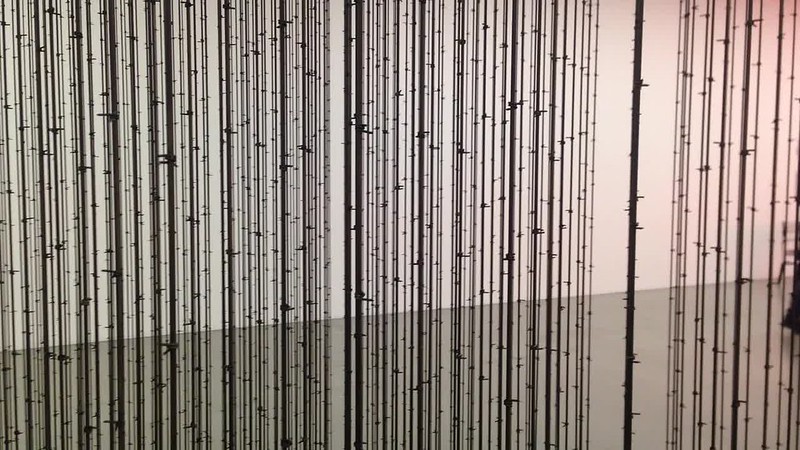

Mona Hatoum “Quarters”, 2017

Mona Hatoum “Quarters”, 2017

ALL IMAGES: installation view, photo: dotgain.info, Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts

; Courtesy of the artist and the Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts, © the artists

A red glowing globe, suggestively identifying the world in an alarmed stage, is placed in the central hall of the lower exhibition space in Leipzig's Museum of Fine Arts. There are suspended strings made of barbed wire, objects that remind of a burned interior and bombed high-rise buildings – all evoking a post-apocalyptic sentiment in the beginning of an exhibition that brings two well established artists together for the first time: Mona Hatoum, creator of the before-mentioned works, and Ayşe Erkmen, whose video- and installation-based 'green room' and her multi-coloured light installation "Glass works" (2015/2017) employ a strikingly contrasting aesthetic language, have been brought together for a large show titled "Displacements". Addressing both the interior space of the museum and the world outside, both artists employ modes of seriality and the re-purposing of politically charged objects and materials, without being too specific about the exact context of their works. In this interview Frédéric Bußmann, curator of the exhibition, talks about his initial motivation for this show, the challenges of the install and he explains why he found it so important to bring the works of Erkmen and Hatoum together right now.

Anna-Lena Werner: Frédéric, since 6 years you are curator at Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig and have realised various exhibitions on different topics. Have you had a theme that interested you throughout your career or has your research focus changed?

Frédéric Bußmann: As curator in Leipzig I am responsible for art works and exhibitions from the 19th century until contemporary art. I wrote my PhD on a French 18th-century collection, but I was interested in modern and contemporary art, particularly in the relation between art and society, collecting and exhibiting, as well as social and political questions. This doesn’t mean that I only curate exhibitions on this topic of interdependence between the artistic reflection and political or social questions, but eventually this is what I am personally interested in. I do not like ‘political art’; I do not care so much about art on a daily political basis or about political representation. I think art is primarily linked to art, but it's interesting if it's not limited to self-references, and even more interesting if you can understand, by visiting an exhibition or by experiencing art, more about yourself and about the others around you, starting to reflect your own society. It's not so much about activism, but about reflection.

ALW: Prior to working as curator at the MdbK in Leipzig you have been in Munich at the Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, in Paris at the Centre allemand d'histoire de l'art, and studying art history in Berlin. With the experience of all these different places, what do you think are the benefits and what are the disadvantages of Leipzig as a place for contemporary art?

FB: When I moved to Berlin in 1996 the city had already changed a lot since the fall of the wall, but there were still a lot of empty spaces; it was a fragmented city; unfilled voids with so many possibilities. The city was not about being something, but about becoming whatever you wanted to be. There was less economic and political pressure, less control; instead it had an anarchist spirit of unsuccessfulness, which was not identical with failure. Twenty years later I moved to Leipzig and the city was totally different from Berlin. Much smaller and much more concentrated on itself in a special kind of Saxon provincialism mixed with nostalgia of a former metropolis. But I felt the same spirit of the uncompleted, the non-self-contained, with a lot of empty and cheap spaces. Since, the city has grown and became more attractive for all kinds of creative people, and especially for artists because they can still – things are changing – afford a studio and a room to live and work. As an artist you have a perfect situation here. There is the art academy (HGB) and a young and mostly open-minded art and creative scene, plus some galleries, art spaces, museums. All this is concentrated, the city is not as vast as other cities, but I cannot think of any other city in Germany of this size that offers such a diverse artistic scene. But for sure, after a while you need to leave this city again, you need to have contacts outside, you need to travel and get in touch with other artists, collectors, art dealers, curators in other cities in Germany, Europe, the world.

Above:Installation view, Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts 2017, with different objects by Ayşe Erkmen

Above:Installation view, Leipzig Museum of Fine Arts 2017, with different objects by Ayşe Erkmen Below: Ayşe Erkmen “PFM-1 and others”, 1997 / 2013

ALW: If you look back, which exhibition has been the most challenging for you?

FB: Certainly the one we show right now, with Ayşe Erkmen and Mona Hatoum. It took more than two years from the first conception to the opening; we had long discussions in the museum about it. Because the conception follows the leitmotif of 'displacements', we placed their works not only in the regular exhibition space but also in different other levels of the museum, in the permanent collection and outside in the city. There were challenging discussions about the exhibition concept and the catalogue with the artists as well. On top of that some of the installations and objects we show are very fragile and some are technically quite complex, so it took more time to install and more skills than usual to set up the exhibition.

ALW: What encouraged you initially to bring such different artistic positions as Ayşe Erkmen and Mona Hatoum together in one exhibition?

FB: I started thinking about this exhibition in 2015, because I had been interested in both Ayşe Erkmen’s and Mona Hatoum’s work for a long time and I thought it might be a good idea to show them in a sensitive dialogue, which had never been done before. Their works are very different and yet they share some interests. I know Ayşe’s works since her intervention in Münster in 1997 with her famous 'Sculptures on the Air' – since then I appreciate her very intelligent interventions, always adapting her means to the situation, sometimes very subtle, sometimes striking. I appreciate Mona’s work very much since her show at the Palazzo Querini Stampaglia in Venice 2009, where I was impressed by her capability to combine highly sensitive, aesthetic means with a clear narrative, symbolist meanings that are often concerned with the global crisis and conflicts. Both artists engage in situations and spaces that they are invited to, both include the public and the perception in their artistic concept. So I presumed that in different ways their works could be highly appealing to a public like the one in Leipzig, which has – if I may say so – less contact with contemporary art than the one in Berlin, for instance.

Another reason to invite Ayşe and Mona to Leipzig was related to the museum's exhibition program. Since I began working at the museum exhibitions were focused on male artists, mostly paintings, so we – the former director of the museum Hans-Werner Schmidt and I – wanted to change that, responding to the development in contemporary art in general and in the city of Leipzig in particular, which has become younger and more international. That's why we also decided to show two female artists, who work with installations and objects, and who are internationally established. I wanted to set up an exhibition with works that are ambivalent: open to discussion, entailing contradictions, activating reflexion about expectations and identity, as well as about topics that are discussed in the society and media at this time in Saxony. First and foremost this is an exhibition of contemporary art, but some of the works, especially the ones from Mona Hatoum, can be related to topics of migration, resentment, control, and also to racism and identity. This is why I chose the leitmotif of 'displacements', because it includes different levels of understanding the works under a political, psychological and artistic point of view.

Mona Hatoum “Remains of the Day (s version)”, 2016 and below, “Impenetrable”, 2009 (video by artfridge)

ALW: The works from Erkmen and Hatoum are spatially separated from each other. Why did you decide not to place their objects closer, in the same room?

FB: In our first conception we wanted to show both artists in the same room, in the central hall, thus creating a direct dialogue between the artists. We also thought about works, in which they might react to each other. But together with the artists we realised that this would not work; both need their own space for their works, because they follow their own rules. Showing the objects and installations in immediate vicinity could have been to the detriment of the respective works.

Front: Ayşe Erkmen “Glassworks”, 2015 / 2017; in the background: Mona Hatoum "Hot Spot III", 2009

ALW: While Erkmen's works are primarily self-refential and evolve particularly in the discourse of contemporary aesthetics, Hatoum's work is political and references subjects such as violence, the body in relation to society or feminism. How do you read the dialogue of their artworks, now that the exhibition is running and you can see the pieces in exhibition? Where do they contradict and where do they nourish each other?

FB: I don’t think Ayşe Erkmen’s work is primarily self-referential. It's primarily referential to the situation in which her work is shown. In our exhibition she needs to create and define her own space like the ‘green’ room – in which she uses her "Imitating Lines" to determine the whole space as her artistic space; as a kind of artistic workshop. Of course she is very much concerned with the contemporary aesthetic discourse, but so is Mona, perhaps in a different way. Ayşe’s work is presumably less narrative, less obvious regarding questions of politics or gender as you might want to see Mona’s work. But this is what makes this exhibition interesting, I think. We have two different artistic and aesthetic approaches, which reinforce each other without interfering, without mixing everything. I think it’s better to show two clearly distinct artistic positions than two similar ones. At first sight you notice clearly visible differences, but then you might find some shared artistic interests, which is, I think, the integration of the body and the movement of the public. And of course the relation of work and space for some works by Ayşe, such as "Glassworks" or "Half of", but also the whole ‘green’ room, as well as for most of the works by Mona, such as "Impenetrable" or "Quarters". You might find references to conflicts in both artists’ works, for instance at Ayşe Erkmen’s "PFM-1" and maybe also "Row-row" and of course for several works by Mona Hatoum like "Natura morta" or "Remains of the Day (s version)". Having diverse approaches to art and to the perception of art is what this exhibition is about. Different perspectives are important, from the position of the producer as well as of the recipient. This corresponds to the exhibition's leitmotif "Displacements" with different levels of meaning.

Ayşe Erkmen "Half of", 2017 (above) and sound installation "Ewig Dein", 2011 (below)

Ayşe Erkmen "Half of", 2017 (above) and sound installation "Ewig Dein", 2011 (below)

ALW: Both of the artists placed works inside the museum's permanent collection, reacting with different media to the old art or putting their own works in contrast with them. What kind of dialogue do you hope this might create?

FB: When Ayşe Erkmen and Mona Hatoum came for the first time to Leipzig the first thing they did was to have a close look at the collections of the museum and the architecture. Both artists are interested in the space, the architectural as well as the cultural space, and the situation in which they are invited to expose. And both chose, together with us, places in the museum and certain aspects of the collection to which they wanted to refer. Especially Ayşe was interested in the architecture, so she was immediately attracted to the central hall in the first floor, where the architecture of the museum culminates. She responds to this architecture, its open and closed spaces, the views through the different levels and to the outside, its regularity and repetition with her installation "Half of". In "Half of" she reconstructed the central hall in fabric by half of its size and repeated it four more times, each divided by half of the size of the preceding object. With this work in situ she points to the characteristics of the architecture and shifts the perception of this space. At the same time she breaks in a way with the monumentality of the museum space by displacing it and enters a sculptural dialogue with the architecture.

Another work is her sound installation "Ewig Dein" (Forever Yours) in the gallery space where we present Max Klinger’s "Beethoven". She was very interested in the big open space of this room, the atmosphere, the acoustics and of course our collection with Klinger’s sculptural masterpiece. She wanted to intervene here, without being in a visual competition with Klinger. She entered an acoustic dialogue with the monumental Beethoven by installing the sound piece "Ewig Dein", which she created in 2011 for an exhibition in Tokyo: a female soprano sings a canon for three male voices by Ludwig van Beethoven called "Ewig Dein" (1811) and Ayşe then remastered the recordings to create the sound of a canon. But the female voice does not correspond to the original notation of the music, so it becomes tilted or disharmonious. With this slightly off-key female adaption of male vocals she reacted to the very pathetic and heroic representation of the male composer, who is shown in a godlike throne accompanied by much smaller female sculptures by Klinger of "Cassandra" and "New Salome". In my opinion – Ayşe is more reluctant about the interpretation of her works – she is in this way commemorating and commenting at the same time the collection and the social and gender-specific implications of this presentation.

Mona Hatoum’s "Cellules" on the other side were created in 2012–13 in Marseille; we placed the 8 cell-like objects in mild steel and glass on the terrace on the second floor in front of the windows regarding towards the outside and the city of Leipzig. This ‘mantle’ of the museum is constructed of a grid in glass and metal, so there is a correspondence of material and form in the "Cellule"s. Mona Hatoum’s objects are shown in vicinity to two baroque sculptures by Balthasar Permoser. I think this display is perfect, because here again her work, which is characterised by the opposition of cold and warm materials like dark steel and red glass, as well as the geometric grid and organic forms, enters a dialogue with the rigid modernist architecture in metal and glass and the movements and organic forms of the Baroque.

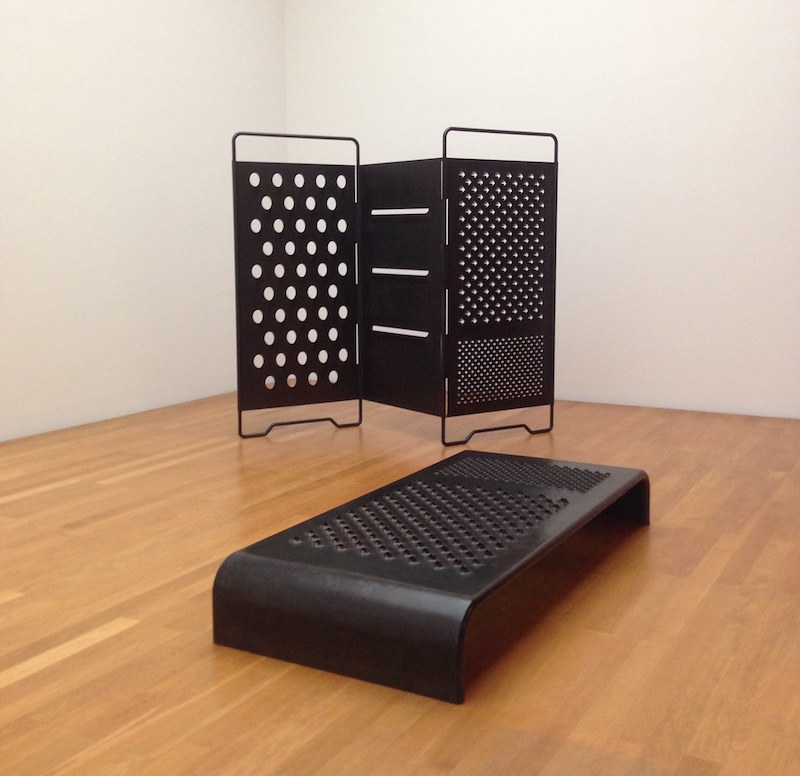

Mona Hatoum "Cellules", 2012–2013 (above), "Daybed" and "Paravent", both 2008 (below) (last image by artfridge)

Mona Hatoum "Cellules", 2012–2013 (above), "Daybed" and "Paravent", both 2008 (below) (last image by artfridge)

ALW: What role do you think does the museum have in regard to education?

FB: Museums are spaces for art and aesthetics, but are institutions of general culture and education as well, what we call in German ‘Bildung’. Furthermore, since the museum is funded by taxpayers it has to play an integral role in the city’s non-commercial culture and as an institution for different kinds of education. It is a privilege to offer different aesthetic approaches by art than any other institution in our society could do. Art is not a mean to education, but the museum can be an open platform for educational topics that can revolve around art works and can include them. This might sound conservative, but I think the education or the ‘Kunstvermittlung’ is a very important duty and chance for the museum, not only to create sensibility for artistic and aesthetic questions, but also about a general culture as one common ground for society. This is why it is important to offer a discursive room for different and controversial opinions, which is the ground for a liberal and open society.

ALW: The MdbK Leipzig has a full program of changing exhibitions. Which one are you preparing next?

FB: Currently I prepare an exhibition with objects, installations and films by Lutz Dammbeck. Dammbeck comes from Leipzig, played an important role in the young artistic off scene in the GDR with his experimental photo and film works as well as his performances. He was part of the artists that set up the so called "Leipziger Herbstsalon" in 1984, one of the first self determined exhibitions in the then very restricted art scene in the GDR, and he migrated to Hamburg in 1986. Since then he became an internationally renowned and successful filmmaker, combining artistic and scientific research in his documentary films. His research focuses on the relation of the individual and the society, first in times of fascism, then socialism and after that on the global order of our current society, the control and determination of humans within larger groups, the influence of cybernetics of identity politics etc. So this exhibition promises to be very exciting, combining different media and topics to a large total installation, a Gesamtkunstwerk, that Dammbeck conceives as what he calls to be the “Herakles Concept” of his whole oeuvre from the late 1970s until today.

Displacements

Ayşe Erkmen and Mona Hatoum

18.11.17 - 18.02.2018

Web: https://mdbk.de

Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig

Katharinenstr. 10

04109 Leipzig

Opening Hours: Tue-Sun 10-18h, Wed 12-20 h

Displacements

Ayşe Erkmen and Mona Hatoum

18.11.17 - 18.02.2018

Web: https://mdbk.de

Museum der Bildenden Künste Leipzig

Katharinenstr. 10

04109 Leipzig

Opening Hours: Tue-Sun 10-18h, Wed 12-20 h