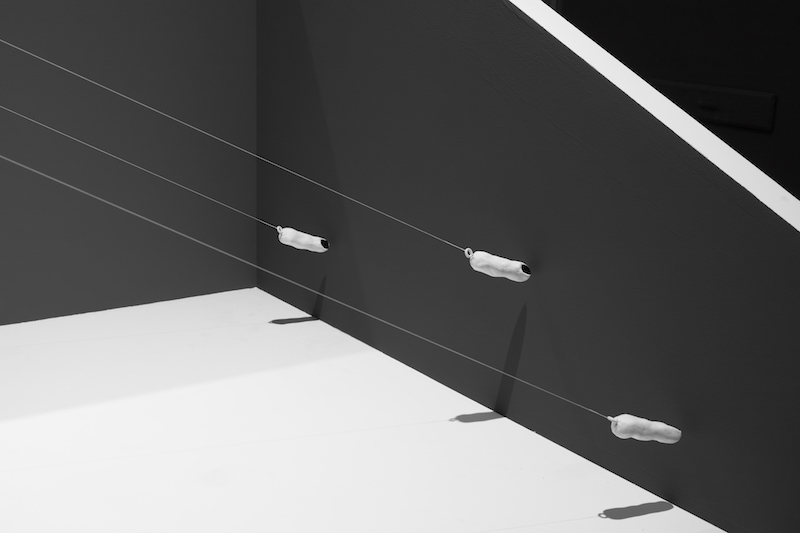

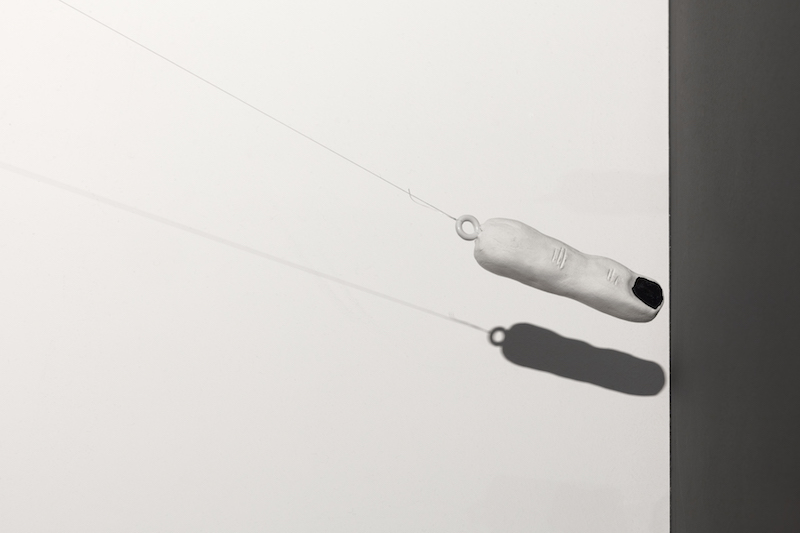

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "The Chariot of Greenwich" (2013) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "The Chariot of Greenwich" (2013) Photo by CHROMA

The work of Columbian-born artist Pedro Gómez-Egaña's poses questions to how technologies affect societies, both historically and now. He explores collective experiences of time and how digital culture changes our attention to life. After having studied at Goldsmiths College and the Bergen National Academy of Arts, the artist lives in Denmark and Norway, where he is currently professor and researcher at the Faculty of Arts of Bergen University. His performative installation “Domain of Things” was one of the outstanding pieces presented at the 15th Istanbul Biennial in late 2017, exploring societies' rising comfort in pleasures of technology while, happening simultaneously, rising conditions of crisis causing people too escape. Currently on display in Berlin, Egaña’s challenging exhibition "The Common Ancestor" at Zilberman Gallery addresses no less than the relation of time and power, and the mechanisation of the world.

Mine Kaplangı: Your recent exhibition “The Common Ancestor” refers to travelling and changing adaptions of the concept of time. How did you approach this theme?

Pedro Gómez-Egaña: More than exploring how the concept of time travels, the exhibition explores different cultural and historical ways of mechanising the world. We think that mechanisation has to do with machines as objects and moving parts that produce goods or motion, but mechanisation can also be a way of thinking about the geographic, the cosmic and the temporal. In line with this, a mechanisation of the world is directly related with the existence of time zones and longitudes. We don’t need longitude or time zones to have an effective experience of time; we also don’t need watches as we have the sun, the seasons and local ways of telling time. But, when the question came up to find ways to synchronise the way the entire globe shares, trades and communicates, then there was a need to produce these artificial lines, this mechanisation of the world.

MK: Can you tell me how your works respond to these thoughts?

PGE: The exhibition takes on this idea of a mechanised world from three overlapped perspectives: firstly, the ancient Chinese story of a show-off mechanical chariot that was magically able to point in a straight line to the South. Then there is the process for establishing a line across the world as an anchor to determine all the time zones of the world, the prime meridian, in London in 1884. The third perspective has to do with the act of pointing, as a physical gesture that encapsulates so much, from drawing attention to something, to exerting authority and establishing territories and lines of conquest.

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "The Chariot of Greenwich" (2013) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "The Chariot of Greenwich" (2013) Photo by CHROMA

MK: You pose the question “Who has the power to claim the beginning, the zero point of time?” – which power structures are you referring to exactly?

PGE: On the one hand, it’s interesting to know that the world used to have many prime meridians. Many cities were their countries’ own 0º degree line. This meant that, unlike today, if it is 3pm in Turkey, it could well be 1:17 in Georgia, and 10:47 in Spain, The was no way to determine global time zones. But it wasn’t a problem until trains and ships began to multiply and travel more and more around between cities and countries. Standardising time was a necessary thing to do, and when London was decided as the official global prime meridian – to much discussion from countries like France for instance, who kept their own prime meridian for several years in spite of the decision – this became a manifestation of a power and influence that Britain already had. It has little to do with cosmic, geographic, or philosophical grounds.

MK: There are on-going philosophical and scientific debates about what “time” means for us, and how this meaning is altered with different cultural or geographical backgrounds. Has this been a concern for you as well?

PGE: Yes, we are still trying to understand what time is and means, but that is also because time is many things. Time is the cycles of agriculture, time is the gestational period of various animals, time is the way our memory “records” more information when we feel threatened or are in danger; time is a fabric that is moulded during hallucinatory rituals. Time is also what happens as a result of the measurement of time, the idea of a civilisation that can communicate and travel from one place to the next.

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "First Topographies" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "First Topographies" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

MK: You launched a publication together with Lotte Laub, Aaron Schuster and Natasha Ginwala along your exhibition. How was the book related to the show?

PGE: I often feel that exhibitions are a great opportunity to punctuate a moment in one’s career and looking back and across. This is what this publication is doing. It explores the show and how it fits within my broader practice and some parallel interests of mine and people in the field. It is not always easy for me to get a broad overview of my work and how it may relate to other cultural and historical questions, so the contributions from Natasha, Lotte and Aaron become especially important. Natasha and I have worked together for some years and she knows my way of working very well, so I appreciate her asking me about things like the status of sketching in my work which is something that I don’t talk about, or show very often. She has taught me to understand sketches from my background as a composer which is something I appreciate very much. Natasha and I also have an on-going conversation about automata and historical technological or magical machines, which also comes into her piece in the book. Aaron Schuster discusses my work from the perspective of sexuality and the reproduction of machines, which I find to be a constant undercurrent in my recent work but one that I could never articulate in such a way. His text has really helped me to understand my use of machines and mechanisms in a new way. Lotte takes on the question of power in the exhibition head on, and makes a very precise contextualisation of the show in relation to my use of literature, and also as a continuation of recent works like "Domain of Things" (2017).

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "First Geometries" (2018)

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "First Geometries" (2018)

MK: There is always a performative element in your practice, even in your sculptural works. There is strong sense of staging, or stage building – creating an atmosphere, and a certain space for the audience to experience the work. Are performative processes playing into your practice?

PGE: Performativity has a very concrete definition in my practice –that of motion. I work with how things move, the character they acquire, how objects or images reveal themselves in time. That, to me, is performativity. The way audiences experience the works, however, I think of more in terms of theatricality. For me theatricality is not so much what happens on stage, but how a space lends itself for a particular kind of focus and engagement. Here, the space, the music, the seating, and the duration are crucial. The most interesting is of course when these two dimension cross, when the motion of objects meets the circumstances for their viewing.

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "Documents: G. Lanchester and HG Wood" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "Documents: G. Lanchester and HG Wood" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "Documents: G. Lanchester and HG Wood" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

Pedro Gómez-Egaña © "Documents: G. Lanchester and HG Wood" (2018) Photo by CHROMA

MK: Defining your work is very challenging. This might be because you work interdisciplinary and with various media, but also because you address almost ungraspable subjects, such as time. How do you feel about describing your practice?

PGE: I agree – I also have so much trouble describing my works. I think that’s because what seems to be at their centre is not the way the components look, but the kind of experience that emerges when it all comes together, a bit in the way we were speaking about theatricality in your previous question. Having said that, I think that it is an interesting exercise to discuss the practices from any of the dimensions that you enumerate. I love thinking about my work from the choreographic for instance, where it is about motion and physicality; or from composition. I am professor of sculpture and installation so this pushes me also to reflect on my work from the perspective of materiality and spatial constellations, as well as the poetics and politics of space.

Portrait of Pedro Gomes Egana; Photo by Randi Grov Berger

Portrait of Pedro Gomes Egana; Photo by Randi Grov Berger

Portrait of Pedro Gomes Egana; Photo by Randi Grov Berger

Portrait of Pedro Gomes Egana; Photo by Randi Grov Berger

MK: What are you working on at the moment?

PGE: I’m excited to be working on a new large-scale commission for Yarat contemporary art space in Baku, Azerbaijan, which will open later this year. The work will be a space within a space where audiences can experience a historical narrative that claims ancient links between cultures from very different parts of the world. A mix between fiction, history and a certain collapse of geographical and cultural references, which I find that resonates very much with our current experience of the world through technology.